SAINTES MARIES DE LA MER

Saintes Maries de la Mer

The 'Saint Marys of the Sea', is a small fishing village located on the south-central coast of Mediterranean France in the Camargue region of Bouches-du-Rhone. Archaeology, coupled with local legends, confirms the site as been venerated as a holy place since the time of the Celts.

Today, many people visit Stes. Maries de la Mer on the coast of that marshy and windswept land around the Rhône delta separating Languedoc and Provence. The village is known as the “spiritual centre” of the Camargue because of the local belief in the miraculous power of the saints.

The Provençal legend tells us that the year 40AD, a boat was launched from Jerusalem, without sails, oars or supplies, and drifted across the Mediterranean until it came ashore at this site. Some think the disciples were forced into a boat without facilities, and then cast adrift, so that they would perish at sea.

This comes from The Golden Legend of Voragine. He says; In the dispersion Maximin, Mary Magdalene, her brother Lazarus, her sister Martha, Martha’s maid Martillam, blessed Cedonius and many other Christians, were herded by the unbelievers into a ship without pilot or rudder and sent out to sea so that they might all be drowned, but by God’s will they eventually landed at Marseille. Not, you notice, at Stes. Maries. The Golden Legend goes on; Mary and the others destroyed the temples of the idols in the city of Marseille and built churches to Christ on the sites. I’m not convinced the Romans would have tolerated that!

The refugees in the boat were: Mary Jacobi, “the mother of James and the sister of the Virgin”; Mary Salome, the mother of the apostles James and John; Lazarus and his two sisters, Mary Magdalene and Martha; St Maximinus; Cedonius, who was born blind and cured, and Sarah, the “servant” of the two Marys, who was also on the boat.

These stories of miraculous sailings are quite common in Christian mythology; St. James was blown onto the coast of northern Spain, and Boulogne in northern France has a legend of Mary Magdalene arriving there in a boat without oars.

Another version of the legend tells us the town was named after only the three Marys who were in a boat; Mary the mother of Jesus, Mary Magdalene, and Mary the sister of Lazarus. (This was in the days when the Church thought that Mary of Bethany and Mary Magdalene were separate people.) With them was Mary Magdalene’s small daughter - called Sarah.

The idea that Mary Magdalene and Jesus were married and had a daughter called Sarah has been rather embarrassing for the Roman Church. In 1982 came “The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail”, linking a bloodline of Jesus with the secret of the village of Rennes-le-Château, and then in 1993 came “The Woman with the Alabaster Jar” by Margaret Starbird. It’s sub-title was “Mary Magdalen and the Holy Grail.”

Margaret had made a great study of medieval Grail legends in the south of France and concluded they contained some underground knowledge that had been suppressed. It has been suggested that if one breaks the word sangraal (old French for Holy Grail) the result is sang raal which in Old French means “Blood royal,” she writes. I have no way to prove beyond a doubt that Mary Magdalene was the wife of Jesus or that she bore a child of his bloodline. But it is possible to prove that belief in this version of the Christian story was widespread in Europe during the Dark and Middle Ages.

Boats of traditional style at Stes. Maries, by van Gogh.

Today, the town insists that that only Mary Salomé, Mary Jacobi, and Sarah, their servant, came in the boat. One story is that Sarah was not allowed on board when the boat was leaving the Holy Land but one of the Marys threw her coat onto the water and it miraculously turned into a raft to enable Sarah to climb on board. Other stories say Sarah may have been an ancient pagan goddess or a black Egyptian woman who was the servant of Christ's mother Mary. (Not Mary Jabobi? More later.)

After landing safely, the group built a small oratory to the Virgin. (Again, history does not back this up; at that time the Virgin Mary had not achieved the high position that she has in the Roman church now.) Some disciples went their separate ways, Mary Magdalene went to Ste-Baume and Martha to Tarascon. Marie Salome, Marie Jacobe and Sarah remained in the Camargue, and were later buried in the oratory.

If you visit Stes. Maries, think of these travellers and imagine the place as it was 2000 years ago. If one arrives by sea, the landmark is the great fortified church, visible from ten kilometres away; between it and the shore is a swathe of flat land now covered with holiday homes, apartments, parks, a bullring, and shops. Two thousand years ago that swathe would have been much narrower, for the water level was higher then.

When the apostles arrived, there would have been no more than a stretch of bleak, marshy shore at the foot of an island or oppidum, on which was a temple to Mithras. Today, you can see an altar in the church, said to be the altar of Mithras and dated 4th century BC. However, this is unlikely, as Mithras was a Persian God who became popular with the Romans, already established in Provence, in the first century AD, not BC. Mithras initiated people by killing a bull above their head and bathing them in blood; I think somebody has linked this with the Camargue bull culture. There is even a statue to one of their bravest bulls on the promenade today.

However, it’s far more likely that this altar was Celtic, for some people say that the oppidum or island was once a sacred site of the Celtic threefold water goddess, and the water source on the island was a holy spring that became known as Oppidum Priscum Râ, after the Egyptian god Râ, father of the sun. This was possibly the Greek influence; The Greeks were here in the Camargue as well as at Marseille.

Then comes a gap in the history although it’s likely that the Romans, after the Greeks, traded with the resident Celts.

Legend says the two Marys here around 43AD and a simple cross of weathered wood marks the exact place. The two Marys caused a spring of fresh water to appear “at the site where the village now stands.” It is true that in the church are sweet water wells, implying that the church was built around them, but this would have been an original Celtic well or natural spring, rather than a saintly miracle.

Then the two saints evangelised the region and lived next to the oppidum of Râ. We are left to assume that the Christianity that they taught was Roman Christianity; but this is impossible, for Roman Christianity only came into being with Constantine in 327AD.

By the sixth century the place had a name. Césaire, the great churchman who lived from 470 to 542, called the place Santa Maria de Râtis when he left it to relatives in his will. The first recorded name of the village was Notre Dame de Râtis - our lady of Râtis - which implies Marian, or Virgin Mary, worship, and a chapel dedicated to her. There was no mention of Mary Salomé or Mary Jacobé, or Sarah, as being buried in this chapel. Which does not mean that they weren’t of course.

The church, outside and in. Notice the Orbs!

It was on the site of this sixth century chapel, possibly dedicated to Sancta Maria de Râtis by Césaire himself, that today’s church was built in the 12th century, and fortified in the fourteenth. In 1936 T.E.Lawrence wrote “Crusader Castles” after a visit to Stes Maries de la Mer with Augustus John. He proved the church’s walls went straight down into the sea with a splayed footing, so that stones dropped bounced out to sea and sank the enemy’s boats.

The church had become a defensive fortress and its nave without side chapels implies it was built with this main purpose in mind, rather than worship. It’s hard for us to imagine today a huge church that was the centre of the village, if not ALL the village, and as well as a fortress and a church, it would have also served as a social centre and a feasting hall. One part of this church is now described as a “Chapelle Haute” but it used to be the guard room. The small main door also tells us it was a fortress.

And inside the church was a well. The original source that was sacred to the Celts had now become a source of water for the soldiers defending the community. A well was essential for a fortress that might be beseiged. (One of the reasons the Cathar castle Montségur fell was because the water supply failed.)

In 1448 René d’Anjou got papal consent to excavate the old 6th century chapel within the church/fortress and he began in the Autumn. He was known as “Good King René” and he had a famous goblet with the words engraved on it; Whoever drinks from this shall see God. Whoever drinks it in one draught, will see Mary Magdalene. His reasons for these excavations are not known.

He found pottery with Christian symbols on it and on the 2nd December, two skeletons, which he declared to be those of Mary Jacobi and Mary Salomé, the two other Marys alongside Mary Magdalene at the crucifixion of Jesus.

The remains of the saints, René said, had been hidden there to hide them from the “Barbarian Invasions” of the eighth century. (This was a popular explanation for the discovery of relics in those days.)

It’s interesting that René d’Anjou knew who these saints were. Maybe there were plaques on the graves naming them; after all, if they were buried at the end of the first century, it’s quite possible that when Césaire’s chapel was built, some four hundred years later, it was not known the graves, with names on them, were there. But who else could have had special graves in that Holy place?

It intrigues me that René d’Anjou, who adored Mary Magdalene, never claimed either skeleton was Mary Magdalene. Perhaps he knew where her remains really were? Or maybe he believed they were at Ste Baume, or he didn’t believe it but didn’t want to enter into competition with these places, he wanted merely to start his own pilgrimage site?

I’ve recently found a reference in the French book, Le bon roi René by Jacques Levron, published in 1972. In 1449, the year after he discovered the skeletons, King René d'Anjou gave to Angers Cathedral the amphore from Cana in which Jesus changed water to wine at the wedding there. René had acquired it from the nuns of Marseilles, who told him that Mary Magdalene had brought it with her to Marseille from Judea. Angers was René’s home and the cathedral was dedicated to St. Maurice, a little known Swiss saint. Odd. However, renovation of the 12th century building began in 1434 - maybe the amphore was simply a gift or relic to start them off with. And Réné knew from the nuns that Mary Magdalene had never been at Stes. Maries because she was in Marseille.

At Stes. Maries the chapel was wrecked by René’s excavations. On his orders, another was built above it to house these Holy relics, which were placed in shrines. Gypsy pilgrimages to the two Marys began the following year, 1449, and have continued ever since. The church became the most sacred place of the Gypsies, who had only arrived in Europe in the early 1400's. They were Romany gypsies, not from Egypt.

So today’s crypt was built above where the skeletons were found. The crypt is to the right of the altar. You can enter it and see the statues in wood of Mary Jacobi, Mary Salomé and Sarah. You can also see the shrines, or relic boxes, of Mary Salomé and Mary Jacobi. These were damaged during the Revolution of 1789, and while some bones remain, these are not the complete skeletons.

Why would the gypsies have been so passionate about these two saints, and Sarah? Sometimes they call Sarah Sara-la-Kali, which means “Sarah-the-black.” Some think it is because they associate Sarah, or used to, with the black Goddess Kali, a statuette of whom is visible in the church. This supposes that the Roma people came from India, where was a goddess of the same name.

Two lovely pictures of Sarah, by Jaap Rameijer

But the Indian Kali was a nasty piece of work, a goddess of sex, death, violence and destruction. It’s thought she represents primal darkness, the darkness that was there before we became spiritually enlightened. There is no relationship between the two Kalis and not all Romanies have their own Kali - except those in the south of France.

Kali from India and the statuette of Kali in a glass cabinet in the church of Stes. Maries.

A book called “Tziganes” (the French call gypsies Gitans) by Franz de Ville, published in Brussels in 1956, has a quote;

One of our people who received the first revelation was Sara the Kali. She was of noble birth and was chief of her tribe on the banks of the Rhône. She knew the secrets that had been transmitted to her. . . The Roma at that period practised idolatry, and once a year they took out on their shoulders the statue of Ishtari (Astarte) and went into the sea to receive benediction there. One day Sara had visions which informed her that the saints who had been present at the death of Jesus would come, and that she must help them. Sara saw them arrive in a boat. The sea was rough, and the boat threatened to sink. Sara threw her dress on the waves and, using it as a raft, she floated towards the saints and then helped them reach land.

This raft story has, it seems, been adapted for later Christian mythology.

A book of legends about Stes Maries tells us the first historical mention of Saint Sarah was made in 1521. She was a charitable woman that helped people by collecting alms, which led to the popular belief that she was a Gypsy. By then, the Roma had been in the region for about a hundred years and they were already Christian. Was this to deny the gypsies story? Equally, Sarah has never been canonised, although they call her Sainte Sarah in Stes. Maries.

As the quote above makes clear, the Roma knew about Astarte that they carried to the sea. In the quote above, they worshipped her during the time of Sarah. But how would they have known Astarte, a version of Aphrodite, if, as history has it, they came from India and not a Greek or Roman country?

Astarte was a Mediterranean goddess of classical times, a female divinity connected with fertility and sexuality; among her symbols were a dove and a star within a circle, representing the planet Venus. In some places she was known as the Evening Star.

She was known by the Greeks as Aphrodite or Artemis. One of her great faith centres was Cyprus, where Aphrodite was born from the waves. In Sidon she was pictured on the prow of a boat, leaning forward with her right hand outstretched, and became the original model for figureheads on sailing ships.

Astarte therefore, was an “Eternal Goddess” of female beauty, but not a mother Goddess. Do we see shades of Mary Magdalene? For the Roma, she was connected with the sea. It seems to me that many goddess legends are coming together here, and maybe the Romanies were right about Sarah and “Stes. Maries de la Mer” - the Marys of the Sea.

Pilgrims started coming to Stes. Maries in the 15th century - the village was mentioned in pilgrims' itineraries, for Mary Salomé was the mother of St. Jacques of Compostelle. (“Jacques” is the French version of James) The route to Compostelle passed through Arles before continuing westwards and the pilgrims only had a short distance to go to see the shrine to she who was the mother of he who they were going to worship.

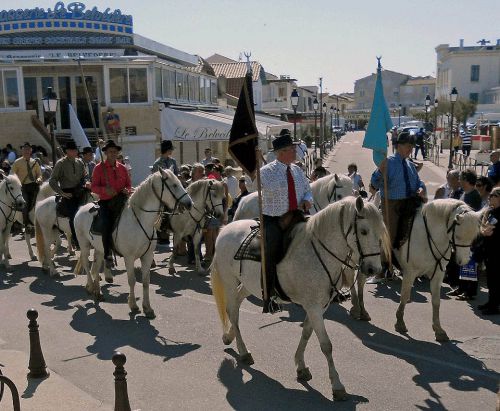

Now many thousands of gypsies flock to the village from the far corners of Europe for the festival of the 24th and 25th of May every year. It is a time of much celebration, of dancing and feasting, but also a time for religious worship and to meet up with friends and relatives they might not have seen since the previous year. Some get married, some have their children baptised.

On the 23rd May, the eve of the festival, the gypsies hold a night-long vigil in the crypt by candlelight. It’s private and closed to outsiders. The next day there is a morning mass, then in the afternoon the ceremony of bringing out the relics of the two Marys and the statue of Sarah at 3-30pm. The church is filled with pilgrims and gypsies and outside are thousands more.

First, the relics of the two Marys are lowered from their storage place high in the church. As the reliquary descends, the crowd, overcome by religious ferveur, reach up their hands, and even hold babies at arm’s length to touch the relics before they reach the ground. To achieve this means one will be healed and receive a wonderful protection from misfortune.

Then the statues of the two Marys are brought up from the crypt and then the statue of Sarah. It is Sarah’s day. Carried on the shoulders of the gypsies and surrounded by pilgrims, Sarah is taken to the sea that carried her the two Marys to her. The crush of people is tremendous, as is the atmosphere.

Photos by Anneke Koremans. See www.panoccitania.com

When they return to the church, Sarah and Mary Salomé and Mary Jacobi are venerated throughout the evening.

On the 25th May, there is a mass at 10am and at 11am, and the statues of the two Marys (not the relics of the previous day) are placed in a boat and, with a grand procession with them, are carried to the beach so that they might bless the sea. A farewell cremony takes place when they are returned to the crypt of the church for another year.

A similar festival takes place on the Sunday nearest to the 22nd October. This one features the Marys and the gardiens, those who guard the bulls in the Camargue, but not Sarah or the gypsies. It’s a festival for those Camargue people who love the bulls.

If you can’t get to Stes. Maries in May or October, it is still worth visiting. On the last Sunday in July is another festival, but not religious in origin. It is the Fête des Vierges (festival of the virgins, in the sense of unmarried girls) started by Frederic Mistral, the great Occitan poet, in 1904. The people then had a great interest in preserving the Occitan culture and lifestyle. Each year the cavaliers or horsemen of the Camargue, who guard the bulls, come to Saintes Maries and the young women parade in traditional Provençal dress. To catch a husband perhaps?

Meanwhile, the anniversary of the day Good King René found the skeletons, the 2nd December, is also a great fête day.

There are many tourist facilities at Stes. Maries, and there is a bullring, as there is a great bull culture in the Camargue dating from pre-Christian days. You will be glad to hear that no bulls are killed nowadays. The “Cours de Cockade” is a game of wits between men and bulls, in the attempt to catch the cockade from the bull’s horns, and the bull often wins. The bulls learn quickly and after several visits to the ring, are banned because they know too much!

In the official guidebook to Saintes Maries de la Mer, there is no mention whatsoever of Mary Magdalene. The church is dedicated to the two saints, Mary Salomé and Mary Jacobi. And maybe the third, Sainte Sarah.

Inside the church, a picture of the two Marys arriving on a stormy day, with Sarah waiting for them

Mary Salomé was the mother of the fishermen disciples, James and John. For a long time it has been assumed that fisherman John wrote St. John’s gospel, but this is not the case, for he was illiterate. Because this Gospel of St. John is the nearest thing we have to an eye witness account, it’s thought that Lazarus wrote it.

It’s also thought Mary Salomé, fisherman John’s mother, was one of the women who "supported" Jesus "of their substance", and went preaching with him, in St. Luke, chapter 8, 1 - 3. She was close to Mary Magdalene, going with her to the crucifixion and with her when Jesus’s body was placed in the tomb.

Mary Salomé is sometimes refered to in the Bible as the wife of Zebedee, the father of John and James. In Matthew 27,56, the three women - the three Mary's - watching the crucifixion from afar, were Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of James and Joseph, and the wife of Zebedee. Mark and Luke also mention Mary Salomé as being at the crucifixion.

But who was “Mary the mother of James and Joseph”? Mary Jacobi? It is assumed so, for the wife of Zebedee was the mother of James and John. Mary Jacobi also appears in Matthew 28, verse 1 as "the other Mary." This mysterious mother of James and/or Joseph appears in the other Gospels, in Mark 15, 40, where it says; Some women were there, looking from a distance. Among them were Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of the younger James and of Joseph, and Salome. By Mark 16, 1 it says, Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of James, and Salome brought spices.

In Luke 24, verse 10, the women were Mary Magdalene, Joanna (the wife of Herod's steward) and Mary the mother of James (who could have been Mary Salomé). But let us remember that Jesus had a brother called James.

In St. John, 19,25, it says, Standing close to Jesus's cross were his mother, his mother's sister, Mary the wife of Clophas, and Mary Magdalene.

There is no Jacobi mentioned in the Bible.

Some Bible scholars are saying that the Mary quoted as the mother of James and Joseph was really the Virgin Mary. She was not defined by the Church as Christ’s mother, who had other sons other than Jesus, because she was supposed to have remained forever Virgin, so it is suspected that they doctored the Bible accounts.

All this makes the nearest identity of Mary Jacobi as - the Virgin. But it is generally assumed Mary Jacobi was a sister of Mary the Virgin, though why her parents would have called both their children Mary is not explained. If we are confused, how much would the people of medieval times been confused, when everyone was called Mary! A possible solution is that Mary Jacobi was a sister by marriage to Joseph, the Virgin Mary's husband. Just as Mary was a common name, so were the names James and Joseph.

And by the time of Good King René the Church had proclaimed that the Virgin Mary was so holy she also had ascended miraculously into Heaven. So no bones found could ever be hers.

Footnote

In modern mystic circles Mary Magdalene is often associated with Stes Maries de la Mer, but the village, its tourist office, its church and its guide book, make no mention of Mary Magdalene. And for myself, I do not believe that she landed there when she left Judea after the crucifixion. It’s my idea that she and Jesus both came to the Corbière mountains to the south of Narbonne.

But that doesn’t mean that they arrived in one place in Languedoc and never moved again for the rest of their lives! No, they had places to go to and people to see. They would have travelled all over the Mediterranean hinterland of the south of France and no doubt visited Stes. Maries de la Mer, as I will explain in an article yet to come.

Inscrivez-vous au site

Soyez prévenu par email des prochaines mises à jour

Rejoignez les 261 autres membres